Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition 1857

Date: 1856-7

Architect: Edward Salomons

Demolished or lost: 1857/8

I had an email this week about an event in Old Trafford that is largely forgotten. This was the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857. The remains the largest temporary exhibition of artworks ever gathered.

The location is now crossed by Talbot Road in Old Trafford, and was bordered by the Botanical Gardens to the north. White City Retail park occupies the area of the Botanical Gardens. Manchester cricket club, now Lancashire had to move a couple of hundred metres or so down the road to accommodate the Art Treasures Exhibition.

The Art Treasures Palace covered an area of two football fields and had its own railway sidings, landscaping and catering arms. The building had the appearance of three large decorated arches. The central and largest arch allowed access to the Grand Central Hall, which was over 700ft long terminating in a stage for a 60 piece orchestra. Behind the orchestra sat a concert hall organ.

As prominent art historian and visitor, the German, Gustav Friedrich Waagen, wrote: ‘I have never seen a building containing such collected works of art so advantageously lighted as this, while the rooms are airy, and of felicitous proportions.’

Oddly, while visitors weren’t allowed to make notes or sketches, they were allowed to touch the paintings. Modern curators would curl up in a ball at the latter these days. Mills closed and people were brought by train to the exhibition from all across the country, some commentators sourly noting how some of the workers scarcely left the refreshment tents.

Date: 1856-7

Architect: Edward Salomons

Demolished or lost: 1857/8

I had an email this week about an event in Old Trafford that is largely forgotten. This was the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857. The remains the largest temporary exhibition of artworks ever gathered.

The location is now crossed by Talbot Road in Old Trafford, and was bordered by the Botanical Gardens to the north. White City Retail park occupies the area of the Botanical Gardens. Manchester cricket club, now Lancashire had to move a couple of hundred metres or so down the road to accommodate the Art Treasures Exhibition.

The Art Treasures Palace covered an area of two football fields and had its own railway sidings, landscaping and catering arms. The building had the appearance of three large decorated arches. The central and largest arch allowed access to the Grand Central Hall, which was over 700ft long terminating in a stage for a 60 piece orchestra. Behind the orchestra sat a concert hall organ.

As prominent art historian and visitor, the German, Gustav Friedrich Waagen, wrote: ‘I have never seen a building containing such collected works of art so advantageously lighted as this, while the rooms are airy, and of felicitous proportions.’

Oddly, while visitors weren’t allowed to make notes or sketches, they were allowed to touch the paintings. Modern curators would curl up in a ball at the latter these days. Mills closed and people were brought by train to the exhibition from all across the country, some commentators sourly noting how some of the workers scarcely left the refreshment tents.

To add to the attraction of the occasion the Manchester Royal Botanical Gardens got involved too. As the official advertisement announced: ‘A communication is opened from the Palace to the Gardens, thus adding to the interest and variety of the Promenade’.

The delivery of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition from conception, through construction, to demolition was jaw-dropping. This was Victorian energy condensed and delivered in its purest form.

Following on from the success of the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and subsequent exhibitions in Dublin and Paris, all focusing largely on industry and science, Mancunians proposed an Art Treasures Exhibition. The idea was dreamt up in February 1856, money raised in March, royal approval granted in May, building at Old Trafford began in late summer and by February 1857 the building was completed. 16,000 artworks were in place by May 1857 and the exhibition opened.

During the next 142 days 1.3m people visited, including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the King of Belgium, the Queen of the Netherlands, Louis Napoleon, Benjamin Disraeli, William Gladstone, Lord Palmerston, Charles Dickens, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Florence Nightingale, Elizabeth Gaskell, John Ruskin, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The delivery of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition from conception, through construction, to demolition was jaw-dropping. This was Victorian energy condensed and delivered in its purest form.

Following on from the success of the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and subsequent exhibitions in Dublin and Paris, all focusing largely on industry and science, Mancunians proposed an Art Treasures Exhibition. The idea was dreamt up in February 1856, money raised in March, royal approval granted in May, building at Old Trafford began in late summer and by February 1857 the building was completed. 16,000 artworks were in place by May 1857 and the exhibition opened.

During the next 142 days 1.3m people visited, including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the King of Belgium, the Queen of the Netherlands, Louis Napoleon, Benjamin Disraeli, William Gladstone, Lord Palmerston, Charles Dickens, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Florence Nightingale, Elizabeth Gaskell, John Ruskin, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Works by artists such as Titian, Raphael, Velasquez, Holbein, Rubens, van Dyck, Gainsborough, Hogarth, Reynolds, Turner, Constable were on show, as were works from the recent Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Indeed the exhibition did much to cement their reputation. Other ‘treasures’ included sculpture, china, furniture, even suits of armour.

An unfinished Michelangelo painting (shown above) was christened The Manchester Madonna after its first public display during the exhibition. It now resides at the National Gallery and depicts Madonna, Jesus, St John and angels.

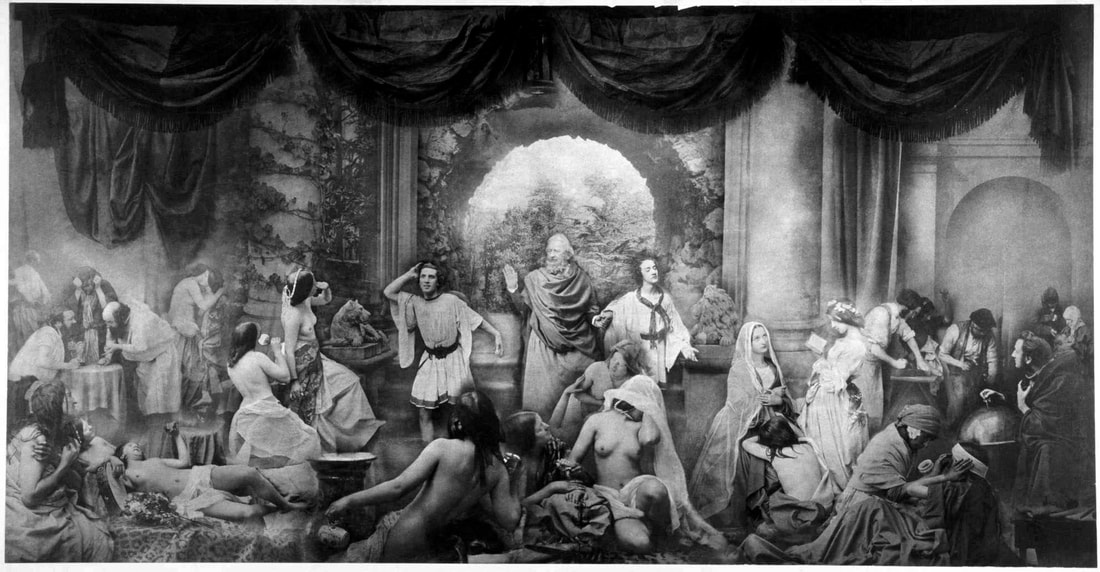

For the first time photography was given prominence including a controversial tableaux piece by Oscar Gustav Rejlander called The Two Ways of Life (shown below). This depicted a pair of young men being offered advice from a patriarchal figure. On one side lie sinful pleasures including lots of topless women and on the other side are virtuous pleasures including reading a good book. It was scandalous at the time but when Queen Victoria bought a copy for Prince Albert the indecency tag faded.

By September the show was over. Within months nothing was left, the vast building had been demolished and dismantled, its 650 tons of cast iron, 600 tons of wrought iron, 65,000 square feet of glass and 1.5 million bricks recycled. The organisers and sponsors of the exhibition, all from Manchester postal addresses, made a small profit of £304 which was used for charitable purposes.

An unfinished Michelangelo painting (shown above) was christened The Manchester Madonna after its first public display during the exhibition. It now resides at the National Gallery and depicts Madonna, Jesus, St John and angels.

For the first time photography was given prominence including a controversial tableaux piece by Oscar Gustav Rejlander called The Two Ways of Life (shown below). This depicted a pair of young men being offered advice from a patriarchal figure. On one side lie sinful pleasures including lots of topless women and on the other side are virtuous pleasures including reading a good book. It was scandalous at the time but when Queen Victoria bought a copy for Prince Albert the indecency tag faded.

By September the show was over. Within months nothing was left, the vast building had been demolished and dismantled, its 650 tons of cast iron, 600 tons of wrought iron, 65,000 square feet of glass and 1.5 million bricks recycled. The organisers and sponsors of the exhibition, all from Manchester postal addresses, made a small profit of £304 which was used for charitable purposes.

There are some permanent reminders of the event. German musician Charles Hallé had assembled a group of musicians to entertain the guests. The response encouraged him to set up the Hallé Orchestra in the city.

The London-based Art Journal praised the exhibition but couldn’t help a snobby dig at the city which had delivered the huge event. It wrote: ‘That Manchester should propose such an exhibition was surprising enough; but how much greater was the marvel that such an exhibition as was actually formed, should have established itself at Manchester!’

Fortunately another metropolitan magazine the Athenaeum was more accurate. ‘Before we can become creators we must educate a race of appreciators who will admire and buy. Nineteenth-century Art has broken from the patron’s drawing room, and appeals to the crowd. The Manchester Exhibition is a vast epitome of Art, ancient and modern – the best of its kind ever attempted.’

The London-based Art Journal praised the exhibition but couldn’t help a snobby dig at the city which had delivered the huge event. It wrote: ‘That Manchester should propose such an exhibition was surprising enough; but how much greater was the marvel that such an exhibition as was actually formed, should have established itself at Manchester!’

Fortunately another metropolitan magazine the Athenaeum was more accurate. ‘Before we can become creators we must educate a race of appreciators who will admire and buy. Nineteenth-century Art has broken from the patron’s drawing room, and appeals to the crowd. The Manchester Exhibition is a vast epitome of Art, ancient and modern – the best of its kind ever attempted.’

RSS Feed

RSS Feed