I WAS followed by a crow today because I had a fish in my hand.

The fish was a fried fish from the chippy called the Hut on Liverpool Road into which my good friend, a Scot, by the name of Steven Lindsay, has in a spirit of civilising progressiveness encouraged the sale of the battered sausage. It’s ‘a belter, a Glasgow delicacy,’ as he describes.

The crow was noble in its devilish darkness, its head swivelling from side to side each time laying a black eye upon me and my haddock. It looked healthy as hell too, with a sheen on its feathers as rich as a polished jackboot. As Mark Garner of Manchester Confidential says, when birds look at you like that, they remind you of nothing less than their ancient relatives, dinosaurs, in this case a big predatory T-Rex.

The crow hopped from wall to wall on Longworth Street never taking its dead vision from me as though Hitchcock were directing it. A woman in her mid-thirties was walking the other way. “It’s following you,” she said with a strange smile, “is it your familiar?” She was dressed completely in black, like the crow. The only difference was she had platinum dyed hair and very black mascara.

The city was looking interesting in the late afternoon winter. It was half three, the light was failing and in the cold air every building seemed outlined in ink against the tarnished silver sky. Yet it was getting a bit scary down on Longworth Street. I swear that as soon as the woman spoke the crow gave her look, bobbed its head, and flapped away arrogantly. I was left alone with my fish and a slight chill down my spine.

The fish was a fried fish from the chippy called the Hut on Liverpool Road into which my good friend, a Scot, by the name of Steven Lindsay, has in a spirit of civilising progressiveness encouraged the sale of the battered sausage. It’s ‘a belter, a Glasgow delicacy,’ as he describes.

The crow was noble in its devilish darkness, its head swivelling from side to side each time laying a black eye upon me and my haddock. It looked healthy as hell too, with a sheen on its feathers as rich as a polished jackboot. As Mark Garner of Manchester Confidential says, when birds look at you like that, they remind you of nothing less than their ancient relatives, dinosaurs, in this case a big predatory T-Rex.

The crow hopped from wall to wall on Longworth Street never taking its dead vision from me as though Hitchcock were directing it. A woman in her mid-thirties was walking the other way. “It’s following you,” she said with a strange smile, “is it your familiar?” She was dressed completely in black, like the crow. The only difference was she had platinum dyed hair and very black mascara.

The city was looking interesting in the late afternoon winter. It was half three, the light was failing and in the cold air every building seemed outlined in ink against the tarnished silver sky. Yet it was getting a bit scary down on Longworth Street. I swear that as soon as the woman spoke the crow gave her look, bobbed its head, and flapped away arrogantly. I was left alone with my fish and a slight chill down my spine.

Writing the time as half three, reminds me of something. I had a typical Northern European misunderstanding on the weekend. I was conducting tours of Chetham’s Library at 1.30pm and 3pm. There were a couple of Norwegians on the first tour who’d arrived a little early. They’d arrived at 12.30pm. This was because they’d rung me in the morning and asked me when the tour was starting. Half one I’d said. In many Northern European countries people think half one is half twelve, an hour earlier, in other words half the hour. In our island logic it clearly can only mean a half hour after the hour.

The Nordic guests were still delighted to come on the tour of these almost 600-year-old buildings: as were an American woman and her daughter who were looking up universities in the UK. The daughter wants to do a Masters in building conservation over here. When Michael Powell, the librarian, revealed letters from the Heywood collection signed by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, they shook their heads in astonishment.

The 3pm group loved the buildings too. As Michael, with his trademark sardonic delivery, was entertaining the guests while showing them remarkable materials such as a medieval bible in manuscript from the 1300s and the utterly lovely first edition of Saxtons’ Atlas of England and Wales from 1579, one woman noticed something about her friend. She thought he looked like the founder of Chetham’s School and Library, Humphrey Chetham, so she got him to pose behind Michael’s back and took the picture. “It’s the nose and the eyes,” she said later. David, as her friend was called, seemed happy to go along with the description. He was Humphrey for a day.

The Nordic guests were still delighted to come on the tour of these almost 600-year-old buildings: as were an American woman and her daughter who were looking up universities in the UK. The daughter wants to do a Masters in building conservation over here. When Michael Powell, the librarian, revealed letters from the Heywood collection signed by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, they shook their heads in astonishment.

The 3pm group loved the buildings too. As Michael, with his trademark sardonic delivery, was entertaining the guests while showing them remarkable materials such as a medieval bible in manuscript from the 1300s and the utterly lovely first edition of Saxtons’ Atlas of England and Wales from 1579, one woman noticed something about her friend. She thought he looked like the founder of Chetham’s School and Library, Humphrey Chetham, so she got him to pose behind Michael’s back and took the picture. “It’s the nose and the eyes,” she said later. David, as her friend was called, seemed happy to go along with the description. He was Humphrey for a day.

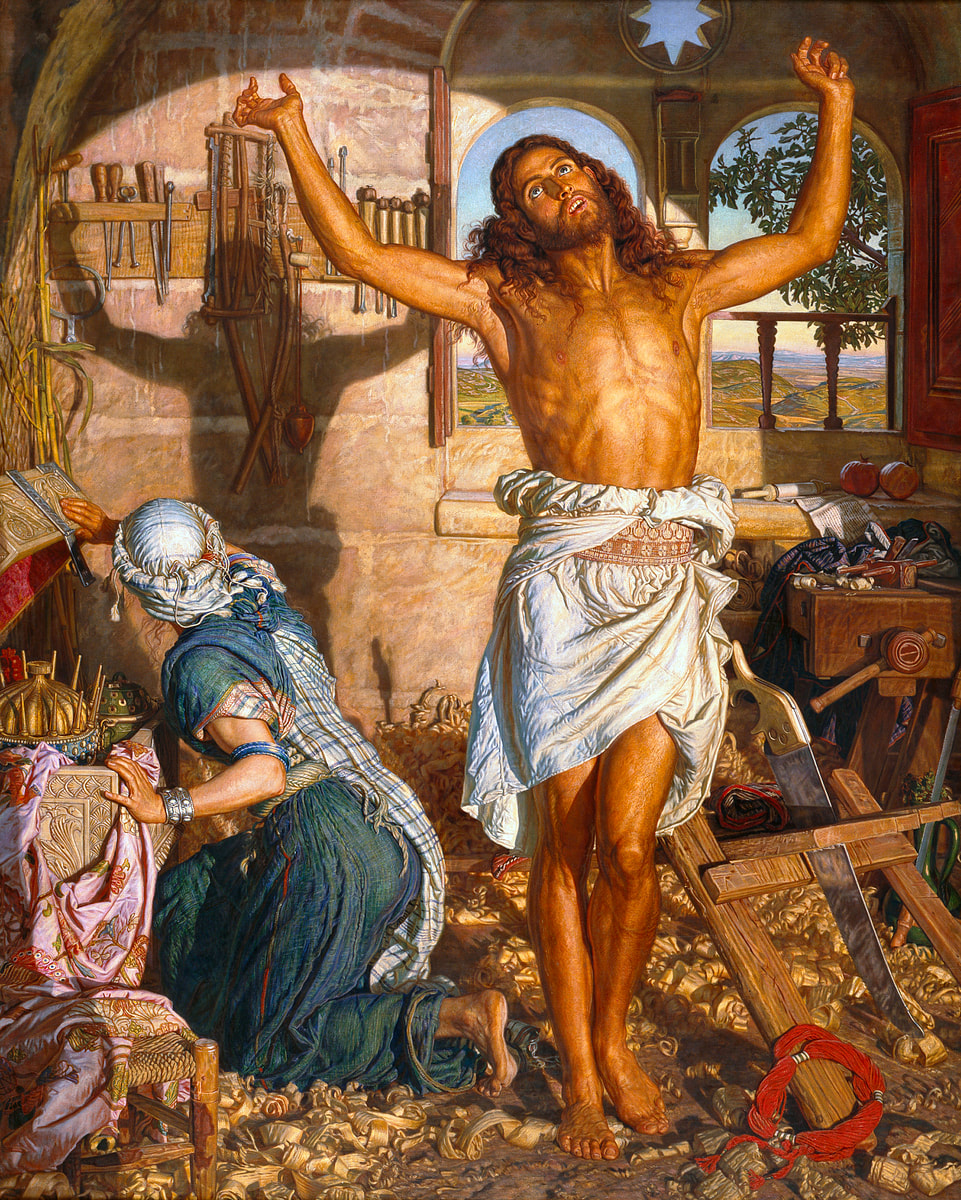

This reminded me of the time when I was taking a large group around Manchester Art Gallery and we stopped in the Pre-Raphaelite gallery. As I was talking I saw four people detach themselves and walk to a Holman Hunt picture. This was The Shadow of Death and features Christ with his arms raised in a Y-shape. It depicts him in his pre-Messiah days when he had a proper job and he’s stretching after sawing wood in his carpenter’s shop, ominously in the Hunt painting, his shadow on the wall behind is reminiscent of the crucifixion.

The wandering four from my group split. One took a picture, while, with Christ’s Y as the first letter, the other three made the MCA of the Village People’s disco blast. It was hilarious - if irreverent.

The wandering four from my group split. One took a picture, while, with Christ’s Y as the first letter, the other three made the MCA of the Village People’s disco blast. It was hilarious - if irreverent.

On that second Chetham’s tour were a father and daughter from Perth, Australia. They have relatives in Hartlepool and had seen Chetham’s Library on an Australian travel programme. Robert had called me in the morning to see if there were any spare tickets. There weren’t, but he seemed desperate to come along and when he said he wanted to drive from Hartlepool to Manchester and back for the tour in a day, I had to say yes.

The English (rather than perhaps the Scots’) sense of distance isn’t long. Two hours in each direction is perhaps the upper limit for most. When I grew up in Rochdale I never went out in Bury, all of six miles distant. Then again there wasn’t much there that Rochdale didn’t have aside from a better fish market and no teenager goes six miles for fish. Even when the crows leave you alone.

Robert’s daughter is studying at a Sydney university. Previously she’d stayed with friends on that side of the country but way outside Sydney and she said: “We’d drive six hours each way to get some city life.” I guided a journalist from Colorado once and he lived two hours from the nearest shop. I like to live two minutes from the nearest shop. And bar. With a national park and the Pennines within ten to fifteen miles. Convenience is so convenient.

The English (rather than perhaps the Scots’) sense of distance isn’t long. Two hours in each direction is perhaps the upper limit for most. When I grew up in Rochdale I never went out in Bury, all of six miles distant. Then again there wasn’t much there that Rochdale didn’t have aside from a better fish market and no teenager goes six miles for fish. Even when the crows leave you alone.

Robert’s daughter is studying at a Sydney university. Previously she’d stayed with friends on that side of the country but way outside Sydney and she said: “We’d drive six hours each way to get some city life.” I guided a journalist from Colorado once and he lived two hours from the nearest shop. I like to live two minutes from the nearest shop. And bar. With a national park and the Pennines within ten to fifteen miles. Convenience is so convenient.

Mind you, thinking of the Aussies, given the state of congestion on Manchester roads at present, it takes six hours to get two miles to The Quays, at rush hour. Something like that. Suffice to say that instead of the projected Sat-Nav time of two hours and forty minutes to get to Manchester from Hartlepool it had taken Robert and his daughter an hour longer.

The Chetham’s tours were the last of the year and so Sue McLoughlin, the heritage manager, and her granddaughter Imogen, provided mince pies and mulled wine. It was all very jolly.

By the way the best question of the week I couldn’t answer came in the Audit Room of Chetham’s. I was talking about John Dee, the enchanter, mathematician and the Warden of Manchester from 1595 to 1605, at the end of his long and slightly preposterous life. Dee was probably the inspiration for Shakespeare’s Prospero in The Tempest. Before Manchester he had been in what is now Germany attempting alchemy, in other words making gold from base metals, the impossible dream of so many dreamers through the ages. He was spying for England too and, by sheer coincidence, through his obsession with symbols, gave himself the code number of 007.

I said something like this to the group, “Ian Fleming who created the James Bond’s MI6 character didn’t know Dee had done this. The inspiration for Fleming’s 007 seems to have come from the number assigned to a code breakthrough for naval intelligence in World War II.”

The a voice came from across the room. “There’s MI5 and MI6, but what happened to MI1/2/3 and 4?”

I had no idea. I have no idea. Next time I see that crow I’ll ask it.

The Chetham’s tours were the last of the year and so Sue McLoughlin, the heritage manager, and her granddaughter Imogen, provided mince pies and mulled wine. It was all very jolly.

By the way the best question of the week I couldn’t answer came in the Audit Room of Chetham’s. I was talking about John Dee, the enchanter, mathematician and the Warden of Manchester from 1595 to 1605, at the end of his long and slightly preposterous life. Dee was probably the inspiration for Shakespeare’s Prospero in The Tempest. Before Manchester he had been in what is now Germany attempting alchemy, in other words making gold from base metals, the impossible dream of so many dreamers through the ages. He was spying for England too and, by sheer coincidence, through his obsession with symbols, gave himself the code number of 007.

I said something like this to the group, “Ian Fleming who created the James Bond’s MI6 character didn’t know Dee had done this. The inspiration for Fleming’s 007 seems to have come from the number assigned to a code breakthrough for naval intelligence in World War II.”

The a voice came from across the room. “There’s MI5 and MI6, but what happened to MI1/2/3 and 4?”

I had no idea. I have no idea. Next time I see that crow I’ll ask it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed