Elizabeth Alker produced, Guy Garvey presented, Rainy City on 6 Music (http://tiny.cc/n7qoi) was a fun piece this week.

I got a cameo role on it, nicely and selectively edited, by my chum Elizabeth. During our interview I found it hard to agree that the weather has any true bearing on the character of Manchester and its people - if the weather is treated in isolation.

It’s a factor in the life here, but you can’t say a disposition to precipitation started the industrial revolution or helped the music scene by keeping people in houses. Indeed, given people are individuals, and so frequently in 2010, from different cultural backgrounds, it's hard to imbue collective character anywhere. Still generisations are very attractive, helping put an order to things. I always love generalisations.

Far more important to me - as the chief element in the art and music of Manchester - is how the physical landscape of mills, warehouses, canals, railways, terraced houses and wasted industrial landscapes impacted on the consciousness of the local and the visitor.

Indeed the urban and rural transformation became so complete in the nineteenth century that you could say the geography was as much a product of the industrial revolution as a yard of finished cloth.

Old south east Lancashire, a place previously compared to Dartmoor in Devon, with twee towns looking like Ludlow in Shropshire, became a place where people became ants amidst vast mills and warehouses. It did this incredibly quickly too - within a generation.

Thus the urban landscape that developed here, I reckon, had more of an impact on character than the accident of climate.

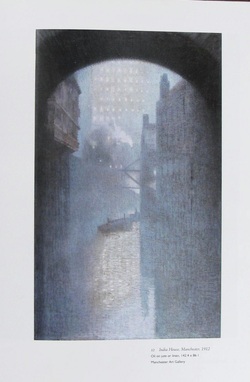

As for art, forget Lowry, the only artist to capture the supposed permanently drenched character of Manchester properly was Frenchman Adolphe Valette. His work in Manchester Art Gallery is simply beautiful.

My favourite is India House from 1912, shown above. In Valette’s vision the physical world is dissolved in water and light, edges soften, colours merge. Beauty is distilled from commercial and industrial landscapes, unregarded views are tinged with an epic, mystical gravity. I could look at that picture and lose myself in it for a long time.

Back to the radio show. It was good to hear Hilary Mantel’s best book ‘Fludd’ being quoted in the 6 Music piece. David Lloyd’s comment about the cricket and playing for Lancashire was the best line in the programme. You'll have to listen to it, to get to the joke.

Funny also that Diane Oxberry, the BBC Radio North West presenter, said: “Manchester’s actually only the ninth rainiest city in the UK.”

Guiding ten years ago I was asked by a Frenchman, “Why do people keep talking about the rain?”

“As a city some people think we are famous for it,” I replied.

“Really, I think your whole country has a reputation for rain not just Manchester,” the man said.

As editor of Manchester Confidential by the way I ban all references of rain from writers. The uninspired Manchester writer will always reach for that get-out clause first. I like to encourage my writers to avoid cliches like the plague.

I got a cameo role on it, nicely and selectively edited, by my chum Elizabeth. During our interview I found it hard to agree that the weather has any true bearing on the character of Manchester and its people - if the weather is treated in isolation.

It’s a factor in the life here, but you can’t say a disposition to precipitation started the industrial revolution or helped the music scene by keeping people in houses. Indeed, given people are individuals, and so frequently in 2010, from different cultural backgrounds, it's hard to imbue collective character anywhere. Still generisations are very attractive, helping put an order to things. I always love generalisations.

Far more important to me - as the chief element in the art and music of Manchester - is how the physical landscape of mills, warehouses, canals, railways, terraced houses and wasted industrial landscapes impacted on the consciousness of the local and the visitor.

Indeed the urban and rural transformation became so complete in the nineteenth century that you could say the geography was as much a product of the industrial revolution as a yard of finished cloth.

Old south east Lancashire, a place previously compared to Dartmoor in Devon, with twee towns looking like Ludlow in Shropshire, became a place where people became ants amidst vast mills and warehouses. It did this incredibly quickly too - within a generation.

Thus the urban landscape that developed here, I reckon, had more of an impact on character than the accident of climate.

As for art, forget Lowry, the only artist to capture the supposed permanently drenched character of Manchester properly was Frenchman Adolphe Valette. His work in Manchester Art Gallery is simply beautiful.

My favourite is India House from 1912, shown above. In Valette’s vision the physical world is dissolved in water and light, edges soften, colours merge. Beauty is distilled from commercial and industrial landscapes, unregarded views are tinged with an epic, mystical gravity. I could look at that picture and lose myself in it for a long time.

Back to the radio show. It was good to hear Hilary Mantel’s best book ‘Fludd’ being quoted in the 6 Music piece. David Lloyd’s comment about the cricket and playing for Lancashire was the best line in the programme. You'll have to listen to it, to get to the joke.

Funny also that Diane Oxberry, the BBC Radio North West presenter, said: “Manchester’s actually only the ninth rainiest city in the UK.”

Guiding ten years ago I was asked by a Frenchman, “Why do people keep talking about the rain?”

“As a city some people think we are famous for it,” I replied.

“Really, I think your whole country has a reputation for rain not just Manchester,” the man said.

As editor of Manchester Confidential by the way I ban all references of rain from writers. The uninspired Manchester writer will always reach for that get-out clause first. I like to encourage my writers to avoid cliches like the plague.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed